By Benjamin Brown

“Pain and pleasure, like light and darkness, succeed each otherâ€- Lawrence Stern

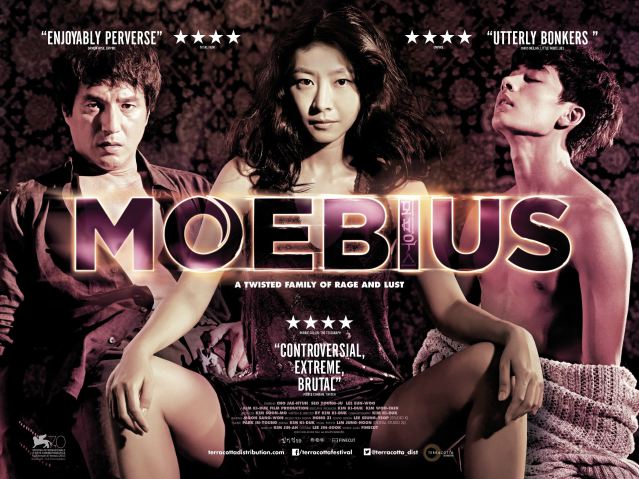

Like Yin and Yang, pain and pleasure are ultimately two sides of the same coin in an emotional vortex of jealousy, betrayal and carnal lust that is the enfant terrible director Kim Ki Duk’s latest cinematic offering, Moebius.

Set in a somewhat benign, suburban milieu this is a strangely twisted take on the domestic melodrama about what may just be the most dysfunctional family in existence. Opening with the teenage son being castrated by his own mother, the Freudian connections only multiply from there when it soon becomes clear that the father is having an affair with a woman who is also the son’s lover. This woman is played by the same actress as the mother, and as if that wasn’t Oedipal enough in its warped merging of familial roles, the father even offers his own penis to his son for a genital transplant. The operation does however have one devastating side effect; the son now gets sexually aroused by the sight of his own mother. This leads to the son effectively assuming the role of father figure whilst the displaced father, in a horrific literalising of Freud’s notion of ‘penis envy’, is rendered inept and can do nothing more but to look on jealously from the sidelines.

So just like Da Vinci’s Vitruvian man, the penis lies at the centre of all proceedings, or in some cases the absence of one. In a most gruesome and toe curlingly corporeal moment, the father, with no conventional means of deriving pleasure instead gets an auto-erotic fixation through scraping and scouring away at his own flesh with a brittle stone.The result is dizzying pleasure quickly followed by agonizing pain, and such controversial, charged images of fetishised, sado-masochistic auto-eroticism brings to mind the actions of Joe in the Nymphomaniac (2013) volumes. Just as with the similarly puckish provocateur Von Trier’s work, there is a mean streak of the most off-kilter, stygian comedy present. As the levels of perversely orgiastic grotesqueries and cartoonish excesses build to a great, carnivalesque crescendo, so to do the laughs.

This humour does however appear from what is a very closed off, hermetically sealed world, and as with Haneke’s Funny Games (1997) the audience is invited to take a step back and question just what it is that they are seeing. As if to compliment such a viewing, the story is dialogue free and told solely through visuals, giving added potency instead to the most subtly nuanced of gestures and glances, and bringing to bear the dictum, ‘actions speak louder than words’. In-fact the only audible sounds are the guttural groans of pain or sonorous sighs of esctasy from its characters, and there is a real sense that the inauthentic, glossy veneer of society has been stripped away to reveal man’s most base of desires.

Whilst in-part being a story about bodily urges, it is also however concerned with the spirit. The virtues of Buddhism are espoused for instance as the teenage son, rather like Joe in Nymphomaniac Vol. 2 (2013), renounces all sexual desire for a life of ascetic celibacy. An act that may be a politically barbed riposte to the increasingly sexualised, commoditised culture of contemporary South Korea, such a character transformation further conforms to the whole Buddhist belief in rebirth. Indeed the whole narrative structure is appropriately cyclical with the title assumingly alluding to how, just like a Mobius strip, events all paradoxically return to a whole by the close.

Despite its self-imposed restrictions, as with the great master craftsman Yasujiro Ozu these limitations are used to its advantage in this audacious and greatly innovative work of devilishly depraved Grand Guignol film-making.

Watch Moebius at FilmDoo (UK & Ireland only)