For some, filmmaking is the best, if not the only, way to keep on the right track in life. It definitely worked out for Kim Longinotto, who is now considered one of Britain’s pre-eminent documentary filmmakers. She won multiple awards for her documentaries at international festivals, including BAFTA, Cannes and Sundance.

Kim Longinotto is a great person to be around, casually drinking tea and dissing Margaret Thatcher (“worst prime minister in our historyâ€) and the latest episode of Breaking Bad (“Jesse makes me feels better for being the person I amâ€). It is hard to believe how troubled her past was – and how much pain she experienced during her nearly 40-year-old career as a documentary director. Yet, she is not one to be hiding skeletons in the closet.

Longinotto is open about her troubled childhood. Her Italian-born father was a strict, authoritarian figure, who knew how “to impress as nice in publicâ€. Her Welsh mother was cold and distant, as eager to keep up appearances as Longinotto’s father, even taking up accent lessons to sound upper-class. As a child, Longinotto mostly kept to herself, often staying in her room all day and reading every book she could lay her hands on. Hardly having any examples of good, decent adults in her formative years, Longinotto says she was terrified of becoming one.

At the age of 15, Longinotto’s first boyfriend – now one of the leading British documentary directors and her lifelong friend, Nick Broomfield, persuaded her to enrol in a film school so she could pursue her dearest dream of making films. But before establishing her career as a filmmaker, Longinotto would be running away from home to live on the streets or hanging out with skinheads, trying to leave her background behind. It took her time to realise she could not become anyone else but herself.

Her very first documentary,  Pride of Place, depicted her draconian border school where Longinotto had spent five unhappy years. “I was so afraid of being caught filming things about the school they did not want me to film,†Longinotto recalls, adding that was the only film she would have had to be lying to make.

She wanted to film horrible punishments that had been in practice at the school, the punishments Head girls would give to other pupils, with teachers pretending they did not know anything. To the headmistress, however, she was showing the world how exemplary the school was.

The release of that documentary at London Film Festival in 1976 led to a public scandal and the eventual closure of the school only a year after – which Longinotto would find out many years after. “In the end, it was a good revenge. It was better than setting fire to it,†Longinotto says, grinning.

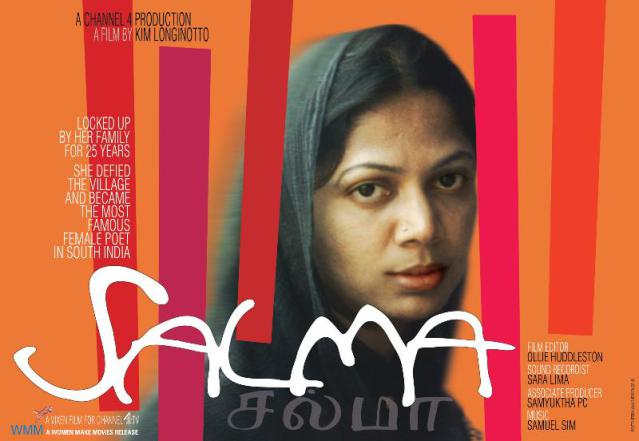

Throughout her career, Longinotto had been pursuing an observational style of documentary filmmaking as opposed to making narrative documentaries, with a notable exception of her last released film Salma.

Longinotto says that she is uncomfortable with making the subjects of her documentaries do something just for the camera, and she would always prefer to give them the freedom of getting on with their lives as they want to – just as she does. “[While making a documentary], we are like two teams working on one project,†Longinotto observes. “I want them to feel it is as much their film as it is mine.â€

This is something that is easier said than done, she adds. While Longinotto was filming Rough Aunties in South Africa, for which she would later win a Grand Jury Prize at Sundance 2009, a little boy was killed in a terrible accident in a community she was working with. “It was incredibly painful,†Longinotto says. “Sometimes I feel like a monster for not stepping in, being forced to film those accidents instead. It’s odd.â€

Longinotto is very protective of people who become the subjects of her documentaries, and says she would always stop filming if she was asked not to. She doesn’t believe in making research before doing the documentary that includes making friends with the people a particular filmmaker wants on camera, though. “I resent it, when filmmakers try to get people to confide in them and then ask them to repeat some information in front of the camera. Are you filmmaker or a friend? I try to be both at the same time.â€

Sometimes people wonder why documentary filmmakers and activists devote so much attention to women, Longinotto says, reflecting on her films that center on women’s issues all around the globe. She finds it very odd that people still find it unusual [making a woman a center of a movie], even in 2014.

“I film women who are survivors, rebels, who stand up against tradition,†Longinotto says. “I’d love it if there were a different mentality [towards women] in our culture.â€

Two years from now, it will be Longinotto’s 40th anniversary as documentary filmmaker. She says that she does not feel there is any difference between making a documentary in 1976 and in 2014. “It’s just as scary as it was the first time,†Longinotto says.

Longinotto will release a new documentary, Dreamcatcher, next year, which will tell a story of Brenda, who had been a prostitute for 25 years before breaking free, being forced into that business at age 12. Longinotto also served as the director for Love Is All, a 2014 documentary on history of the courtship tradition in England since 1898. The film, put together by Longinotto’s favourite editor Ollie Huddleston, will  feature exclusive archive footage and will be set to Richard Hawley music.

There are still challenges to Longinotto as a filmmaker that she does not feel up to. Even though she fell terribly ill with typhoid while filming Sisters in Law in Cameroon, one country terrifies her even more than a near-death illness. “I would love to make a documentary in Pakistan, but I am really afraid to go there and be kidnapped,” she says.

“But there are always more battles to fight.â€

Kim Longinotto’s Top 3 Film Recommendations

“Fucking Amal”, 1998. Dir. by Lukas Moodysson

“Lives of Others”, 2006. Dir. by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck

“Wadjda”, 2012. Dir. by Haifaa Al-Mansour

Watch our three-part exclusive video interview with Kim below.

One thought on “INTERVIEW: BRITISH DOCUMENTARY MAKER KIM LONGINOTTO”