By David Pountain

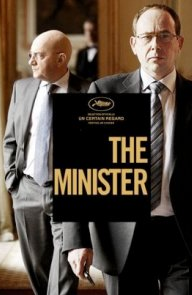

Directed by Aleksi Salmenperä

Gothenburg Film Festival review

Even when made with the best of intentions, environmental fiction can be a chore to sit through, often providing the best examples of how good messages can make for bad art. The problem is often the tendency of green-minded filmmakers to telegraph their opinions in the most direct, judgemental and absolute ways, suggesting a confusion between discourse-friendly social-mindedness and artless moral-pushing. Audiences who went into Ferngully to see the cute fairies and anthropomorphised lizard were probably left bitter by the film’s ‘man is the deadliest animal of them all’ strain of proselytising, assuming they were convinced to care at all – and lest we forget, the worst scenes of Avatar are generally the ones where the film actually tries to be about something.

Some have chosen to overcome this grating preachiness through daunting spectacle, such as Roland Emmerich, whose ludicrous epic The Day After Tomorrow brings the effects of climate change to cartoonish extremes. The Mine takes the more graceful yet grittier route off the pedestal, delving right into the thick of the cold office dealings that facilitate almost every environmental hazard in order to uncover the inner mechanisms of such corruption. Like the Adam McKay’s recent Oscar contender The Big Short, it deconstructs a recent real life outrage to demonstrate how everyone had their reasons, albeit mostly of the selfish kind. Without letting its subjects off the hook, The Mine reveals just how easy selling out can be under tense and wearying circumstances.

The mine in question is a huge nickel source in Lapland that belongs to Finnish company Talvivaara. With the intent of making a living for his family, the intelligent but inexperienced Jussi takes a job overseeing environmental permissions for the project and it soon becomes apparent that some pretty substantial corners are being cut. In order for development to continue, Jussi is pressured into overlooking the fact that Talvivaara’s work is having a toxic effect on local waters. For those unfamiliar with the true story, The Mine establishes right from the start that the plans of Talvivaara and CEO Pekka Perä eventually fall through, leaving it to the bulk of the film to lay out the web of affiliations and systematic manipulations that can facilitate such neglect.

Director Aleksi Salmenperä creates a grimly cloistered world in which immoral decisions can be defended on a purely practical level. The environmental repercussions of the project, as well as the resultant local and media backlash, seem too distant to register emotionally in a system where loyalty to your employers and business partners is paramount. So while big boss Pekka is the film’s most obvious embodiment of the pragmatic deception that drives reprehensible acts, it’s pretty clear that he’s no lone boogieman. It’s telling that the least interesting moments in The Mine are usually those that depict the domestic tensions catalysed by Jussi’s moral crisis. The film is at its most persuasive when it stays wholly sealed within the business bubble, where convenient mental blind spots and selfish calculation are consistently reinforced for the sake of PR and profit. Viewers may not always be able to follow what exactly is going on but the emotional pressure cooker of the working world still feels vivid.

The potency of this pressure to succeed adds an exciting layer to the film, making the audience almost complicit in the corrupt actions depicted. Because of the contained atmosphere that the film creates, there are times where we almost want Talvivaara’s business venture to triumph despite ourselves. It is in the conveyance of this factor and many others that The Mine’s content can be a fair bit more interesting than its delivery. The ominous synths and nagging percussion that characterise the film’s soundtrack intrigue sporadically but otherwise Salmenperä tends to play it a little too safe in his portrayal of office space drama, neither giving his style over to the inherent gloom and cynicism in any particularly bold way nor ironically playing on the slick surfaces that big businesses seek to maintain.

Visually, The Mine does however step up its game whenever it journeys into the great outdoors, depicting the expansive woodlands and intrusive development with sufficient dread and dinginess. Arguably the film’s best shots come with the pensive opening pan over an untouched landscape and the ghostly post-desecration footage of an empty, ruinous site that finally confirms and concludes the fall of a giant. Through such lamenting imagery, it is clarified that just because Talvivaara and their political and corporate associates didn’t get away with their plan, that doesn’t mean this story had a happy ending. And through the intimidating phone calls, shady meetings and ethical compromises that we witness in between this all, it is made maddeningly apparent just how likely it is that this could all happen again and how little has been resolved.

Discuss The Mine on FilmDoo.com.

Recommended Viewing on FilmDoo:

(UK & Ireland only)