By David Pountain

Sometimes a man can be so many things at once that it’s difficult to pin down just what he really is. It took eight years and a Golden Lion award for Takeshi Kitano’s native Japan to take him seriously as a filmmaker, having previously been fixed in their perceptions of him as a famous comedian and TV host. Internationally, many of us will think of him as that guy in Battle Royale or, in the case of us Brits, the namesake of that wacky Craig Charles gameshow that no one ever seemed to win. All of these assessments are, of course, correct but each is only one part of the elephant.

This elusiveness transfers to his output as a director. While Kitano seems enamoured of the worlds of cops and gangsters (namely Japan’s yakuza), he tends to withhold the conventional set pieces and story arcs which could have brought the filmmaker a more consistent mainstream or grindhouse audience in both the east and the west. He isn’t afraid to pepper his work with a little sentiment but he’ll often undermine these same moments with sardonic humour and shocking fatalism. When he does take a page from his other major profession and directs an outright comedy, the result is usually thought of as one his weaker works as a filmmaker.

Even in his performances, Kitano can be hard to get a read on, remaining distant and stone faced through most of his starring roles. The use of obscure protagonists is just one way in which the filmmaker regularly denies his audiences an easy character-based point of subjectivity, others being the employment of unconventional storytelling and pessimistic worldviews. He’ll go from goofball to potentially suicidal in the blink of an eye and it’s up to the viewers to keep up.

Could it be that his entire zigzagging, label-defying career is an extension of his one infamous foray into videogame designing, the legendary 1986 troll-job Takeshi’s Challenge that misanthropically pushed gamers to give up in frustration and actively mocked any player who actually did persist to the game’s end? Let’s hope not, because this list of his ten best works as a filmmaker was put together not just for the intent of giving a few recommendations from the body of work of one hell of a talent but also to probe the underlying logic and philosophy of his pictures, perhaps bringing us a little bit closer to his mysterious, multi-faceted mind and maybe – just maybe – getting some kind of a vague idea of what exactly this guy’s deal is.

10. Kids Return (1996)

Kitano’s sixth feature is a coming-of-age film that focuses on two knuckle-headed individuals whom the genre would usually see relegated to the status of comedic side-characters. Class clowns on the few instances of actually being in class, the cruel and humorous antics of Masaru and Shinji make them a source of merely detached amusement to many of their schoolmates, leaving them without a community or a purpose while the consequences of their bullying and anarchy start to take hold. The two should’ve-been underdog stories that emerge from this setup (Masaru in the yakuza and Shinji as a boxer) are characterised by disappointment, wasted potential and humiliation, each concluding with its own foreseeable anti-climax.

But as the film’s similarly arced side-plots would indicate (the victim of Masaru’s bullying who later gets a dead end office job; the dedicated comedy duo that performs to near-empty venues), losing just might be an inherent part of both adolescence and adulthood, regardless of whether you spent your formative years diligently studying or making an anatomically correct model of your teacher as part of a prank. The narrative setup of The Kids Return may not be particularly accommodating of the strengths of the director at the time (Dolls-era Kitano could’ve made something great from this) but it’s this weary, defeated outlook of the battles of youth and their relation to the treacherous ladder of the working world that makes this film a worthy expansion of Kitano’s challenging cinematic vision, not least because it was an early case of Kitano offering some kind of hope post-failure, suggesting the vague possibility of its characters learning from their mistakes as they make a second attempt at escaping the rut they’re in.

9. Zatoichi (2003)

Kitano has always had a knack for mixing grave stoicism with goofy humour so, if anything, the samurai genre would appear to actually be a more conventional fit for him than his beloved yakuza cinema. This blood-spattered lark, however, belongs to a whole other category to the Kurosawa classics. Every bit as aware of its own artifice as previous films Dolls and Brother (albeit to simpler ends), Zatoichi (sometimes packaged under the title, The Blind Swordsman: Zatoichi) is a period film of unapologetic modernity, applying digital cinematography and a dramatic electronic score to cartoonish spectacles of CGI violence that are beaten in the domain of invigorating choreography only by the film’s exuberant dance finale. This may well be Kitano’s biggest crowd-pleaser, not in spite of its outward eccentricities but because of them.

Of course, Kitano’s long established sensibilities dictate that it can’t be all just surface flash. The film holds a refreshing structural autonomy, going off on whatever out-of-chronology tangent it sees fit. Kitano seems concerned with neither telling a coherent story nor building a fully fleshed out world but rather building a sense of the world.

Corresponding to the condition of its eponymous hero, Zatoichi conveys the clarifying power of the senses beyond sight, notably sound. Much like Zatoichi himself thrives in the seemingly random game of dice just by carefully listening, the film finds order and rhythm in the incidental, turning the sounds of peasants toiling in the field into comical percussion routines. At the same time, visible surfaces are consistently revealed to be deceptive, from the man disguised as a geisha to a last-minute twist that places the audience as the predominant chumps for thinking they know what’s what. In doing so, the film promotes a more clear-minded engagement with reality that is neither dependent on shallow assumptions nor overwhelmed by the seemingly inscrutable chaos of the world.

Just to be clear though, this is still the film where Kitano impales two men on his sword at once before running them into a tree.

8. Outrage (2010)

With its grimly comic violence, brisk pacing and standard gang feud set-up, the first twenty minutes of Kitano’s long-awaited return to yakuza cinema may leave the impression that the director has finally started capitulating to the conventions of the genre. If Outrage subverts these assumptions in the remaining hour and a half, it’s not by toning down its action for a return to the more meditative approach of Kitano’s ‘90s output but by maximising its brutalities to bursting point.

While this is hardly the first Kitano film that operates by an almost obsessive sense of purity, that purity had previously been one of quiet, hypnotic stasis. Outrage defies this pattern by remaining steadfastly focused on chaos and bloodshed to deliberately numbing effects. It’s an affectionless journey through the criminal rat maze that offers the viewer no moment of comfortable clarity, no fleshed out protagonist to latch onto and no discernible narrative beyond a chaotic string of double-crosses and murders.

Any attempts to maintain a bird’s eye view of the film’s dense web of fake alliances are quickly thwarted by this overwhelming disorder, dryly revealing the absurdity of trying to sustain any semblance of honour and civility in such a mutually hostile environment. Brotherhood is a convenient illusion mutually upheld by power-hungry, vindictive thugs and to expect the traditional notions of mob loyalty and professionalism to hold weight would be like throwing a dozen angry chimps into a boardroom and expecting them to have a civilised meeting.

Meanwhile, as the body count and severed finger tally each reach parodic levels, both the viewer and the characters have become so accustomed to the rampant violence that the sound of one’s colleagues getting blown up in the next room isn’t even worth flinching at. By inflating such carnage to the level of bitter sketch show silliness, Outrage moves beyond the limits of what either a gangster film or a Takeshi Kitano film should be and, in doing so, it’s a more original and subversive mob movie than you’d think this decade could yield.

7. Boiling Point (1990)

Kitano’s slippery sophomore work opens with a quiet defeat for junior batter Masaki that pensively sets the tone for the young man’s life beyond the baseball field. Played by an older-than-he-looks Yurei Yanagi, the ungainly, unmotivated Masaki exhibits the despondency and removal of many a lead character that Kitano himself would play, only with a greater outward vulnerability that makes his seeming indifference to the dangers of the mob feel more immediately concerning than, say, Nishi’s indifference to danger in Hana-bi. Masaki may have more going on in his head than his dim bulb appearance would suggest yet, as one pivotal confrontation with a yakuza goon makes clear, this kid really doesn’t know what he’s doing, setting off a series of events that land him and those around him in strange and hazardous territory.

That the foolhardiness of the whole situation sinks in only gradually for the viewer is a reflection of the ennui that affects Masaki and his fellow youths. From the one boy who keeps getting his face bloodied on the road to another who keeps getting overtaken, Boiling Point poignantly captures the daily embarrassments, failures and general awkwardness that adolescents and young adults suffer in the face of more experienced, authoritative elders.

As an actor, Kitano only enters the fray after a mid-film shift in perspective, playing one of his most unpleasant, perilously unpredictable characters. His often contemptible actions as the thuggish Uehara bring the audience ever deeper into the film’s dire rabbit hole, evolving Masaki’s story of misguided youth into a bleakly comic, nihilistic odyssey that evokes ‘70s Sam Peckinpah and predicts late ‘90s Coen Brothers. Featuring what is surely one of the most disturbingly underplayed rape scenes ever captured on camera, Boiling Point delves into a world of cold pessimism and oppressive meaninglessness, yet it somehow remains one of Kitano’s more tenderly human works.

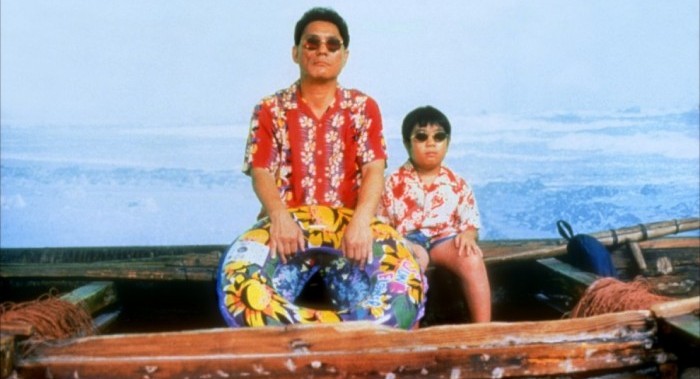

6. Kikujiro (1999)

Even in his more ‘serious’ pictures, Kitano can be a remarkably deadpan comic director, often punctuating scenes of sentiment and sombreness with blunt, amusing reminders of the more graceless facets of the human experience. Man’s fallibility and belligerence consistently expose any sense of order and convention to be fleeting or illusory, sometimes to the point of self-destruction, as in 2010’s Outrage. But it isn’t all bad news. The warm-hearted Kikujiro, for example, manages to find solace in this chaos, withholding the traditional model of the family unit in favour of a more subjective, open-ended vision of companionship and fulfilment. Kitano’s Kikujiro is not anyone’s idea of a good father figure. In fact, he’s an erratic, child-like bully. But since neither mother, father nor angel is watching over the lonely and oblivious young Masao, this hilariously piggish fellow may be the secular, deeply flawed alternative to a godsend.

On the unlikely pair’s futile journey to unite Masao with his mother, various new, transitory families form and dissipate. Yet the assortment of misfits and wanderers they encounter all leave a profound impression on the naïve little boy, with the leisurely pacing putting more emphasis on the joy of meeting and knowing than the pain of departing. Kitano regularly integrates other art forms into his features, be it painting (Hana-bi), puppetry (Dolls) or music (Zatoichi), but here he creates a broader celebration of the resourcefulness of people and their ability to create wondrous things. As for Kikujiro himself, he may enter the film as a selfish, irresponsible schmuck and arguably hasn’t changed much by the end but it’s hard not to be touched by his well-intentioned attempts at finding meaning and purpose amidst the marvellous series of accidents and conflicts that is life.

Read our review of Kikujiro here.

5. Brother (2000)

Any attempt at a commercial breakthrough in the US for the Kitano brand of crime cinema may well have been doomed from the start but, with the underrated Brother, at least the director failed with delirious style, delivering a dazzling and wickedly clever spectacle of LA-based artistic self-destruction. Behind the film’s cookie-cutter gang warfare narrative lurks an underlying meta-commentary of miscommunication and conflicting standards as the cultural meetings and power struggles in front of the camera evoke a creative crisis occurring behind the camera.

Much like the man who plays him, yakuza officer Aniki is on new, alien ground, trying to establish himself amongst people who don’t really know who he is. The calm pacing and lonely stillness of the opening minutes quickly establish that what we are watching is more a Kitano film than it is an American film, though even the feature’s title seems to acknowledge deep-rooted ties between the former and the latter. But from the moment Aniki integrates into a local gang, an operatic push and pull of identities starts to erupt.

The battleground being fought on here is one of cinematic and cultural sensibilities, especially with regard to representations of bloodshed. The various scenes of finger-chopping, suicide and teamwork-based massacres are sufficient evidence for the uniting power of (fictional) violence, bringing together separate factions and races under a bloodstained banner. Yet the sharp and often ceremonial violence of the Kitano playbook are eventually edged out by explosive sequences of Hollywood bravado as Aniki’s multi-ethnic brotherhood goes to war with the local Mafia. As the Godfather-esque series of purges and revenge strikes begin to envelop the film, Aniki’s status within the drama becomes increasingly marginalised until he’s reduced to a quietly accepting witness to his ambitious venture’s demise – a situation no doubt identifiable to any naïve visionary who has seen their own project slip from their hands and into the meat processor of showbiz.

But make no mistake, Brother is not an angry or despondent treatise on American cinema but a playful and bittersweet tribute to gangster cinema on a universal level, providing a complex and vastly entertaining mingling of two worlds that wouldn’t have been quite so poignant had it ever managed to happen again.

4. Dolls (2002)

When the ‘bound beggars’ of Dolls are first seen walking through the blossoming treescape of Kitano’s most visually ravishing film, their ceaseless journey and the umbilical rope joining them together are causes for derision from the couples and friends who watch them pass, all of whom overlook how this odd behaviour merely literalises the way each one of us conducts our existence. In a film that turns a melancholic eye to the various ties that bind, it is this connection between representation and reality (or metaphor and subject) that makes Dolls one of its director’s most profoundly personal works.

The Bunraku performance that introduces this story immediately foregrounds its inherent fictionality but also draws attention to the lives and universal truths that these dolls and their corresponding actors channel. Similarly, the semi-vegetative Sawako may appear oblivious to anything beyond that which is immediately in front of her but – much like the simplest of fables can speak volumes about the world around us – her attentions grant greater meaning to small and dispensable things: a plastic mask is seen as the fully formed figure from her nightmare, a pink little ball might as well be the whole moon.

These self-reflexive observations grant richly ambiguous layers to the film’s three distinct tales of guilt and devotion, rendering the tragic, lonely limbos in which each character resides all the more resonant. Kitano’s hypnotic film tenderly posits that while we may have neither puppeteers’ hands nor a prewritten narrative driving our actions, we’re all ‘dolls’ in the grand scheme of things – small, fragile and subservient to the emotional pull of the people and things we feel the closest to.

Read our review of Dolls here.

3. Violent Cop (1989)

After almost two decades of Dirty Harry and Death Wish films, and their various grindhouse rip-offs, Kitano’s astonishingly grim directorial debut is the sight of cinema’s dreams of lone maverick justice finally keeling over from exhaustion. From its stark title onwards, Violent Cop exudes a weary disillusionment, staring blankly out at a pitiless urban landscape corrupted beyond salvation, and solemnly inwards at a defeated and humiliated soul governed by inexpressible rage. With no tangible solutions in his grasp, Kitano’s detective Azuma is reduced to impotently flailing out at his surroundings in a clumsy attempt to slap some humanity back into the world.

While the violence of subsequent pictures like Hana-bi would come in sharp, exclamatory bursts, here it is delivered in sad, whimpering sequences that become increasingly pathetic the longer they go on. There’s no satisfaction to be found in any vengeance Azuma manages to wreak because the evils committed by cop and criminal alike feel disturbingly banal, from the chuckling middle class kids who harass a homeless man in the opening minutes, to the grizzly, ingeniously underwhelming final shootout that prefigures the pessimistic conclusion to Reservoir Dogs, only without the Tarantinian wink to the audience to let them know that it’s all in good fun. Kitano would go on to create more complex works than his debut but it’s the tunnel vision perspective of Violent Cop that makes it so harrowing. In the face of the onslaught of horrors and injustices witnessed in Azuma’s day-to-day life, no other worldview feels possible beyond the lonely misanthropy that engulfs the violent cop’s mind.

2. Hana-bi (1997)

While a case can certainly be made that Kitano has never directed a single outright ‘thriller’, none of his crime flicks seem more averse to conventional blood-pumping drama than the film that finally got people in Japan to take his work as a director seriously, Hana-bi. With its sense of loss established and accepted from the start, this is a film that leaves itself with nothing to fight against, only events and ideas to observe, contemplate, lament or appreciate. Having spent half his directorial career so far dealing with yakuza, Kitano has little patience for the various punks and criminals that try to get in the way of his character Nishi, brushing them off in sharply edited scenes that sporadically punctuate Hana-bi’s wistful contemplations of eternity. The entire film seems to exist within the final chapter of a larger story, as retired cops Nishi and Horibe, and Nishi’s terminally ill wife Miyuki, take one last long look at existence and all the violence and beauty it holds.

While Nishi just might be the paramount example of a Kitano lead who remains at a challenging distance from the audience, elements taken straight from the director’s own life betray the intensely personal nature of the film, most notably the final scene appearance of Kitano’s real life daughter Shoko and the many paintings Kitano made in the aftermath of a near-fatal motorcycle accident in 1994. These paintings are just one means by which the film indulges in obsessive recreation and repetition both in the context of the film itself (see also the use of a fake police car, fake police uniform and fake gun to rob a bank, and a recurring flashback of a traumatic event) and in relation to previous works (most notably the inescapable parallels between the endings of Hana-bi and Sonatine).

Such backtracks and duplications suggest a cryptic attempt to reassess the world and resolve some nagging issues of the past before shuffling off this mortal coil. In the process, Kitano finally breaks fully from the gravitational pull of gangster cinema and into the creative cosmos as a mature artist in complete control of his craft.

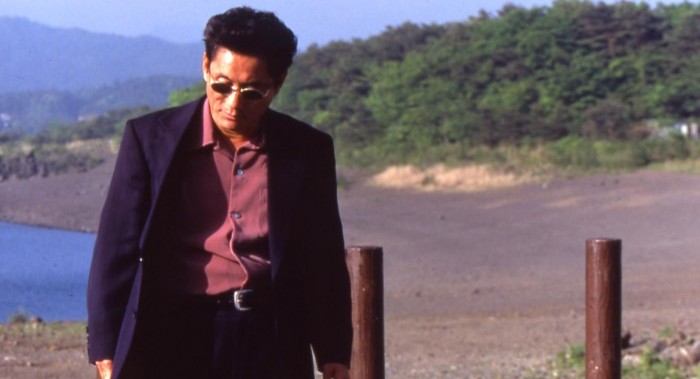

1. Sonatine (1993)

Kitano’s debut Violent Cop may be the bleakest thing the guy has ever been involved in (quiet yourselves, Takeshi’s Castle detractors) but it’s the director’s international breakthrough picture Sonatine that feels the most like an outright philosophical horror film. On a surface level, the film maintains much of the B movie grime of Kitano’s early pulpy work but its style is applied to new, more sophisticated ends, not only draining the indulgence and glamour from gangster cinema but also using the placid frankness of Sonatine’s lo-fi aesthetics to create an emotionally oppressive environment of mental and physical stasis. The streets and docklands of Violent Cop are too gloomy for traditional heroism to blossom; the offices and barrooms of Sonatine are too sterile.

Not that the film doesn’t also give Kitano’s worn-out yakuza Murakawa anything to lose. With suicidal fantasies and underlying enmity suggested in even some of his more playful actions Sonatine’s reticent protagonist never stops feeling like a soul in jeopardy but redemption still feels possible once he and his mostly young and incompetent colleagues retreat to the seaside during a particularly hostile situation. Among the instances of camaraderie and serene contemplation that see Kitano laying the groundwork for the profound meditations of Hana-bi and Kikujiro, the sequence in which a game of makeshift toy fighters is remade using real people stands out as a eureka moment, acting as one of the first, greatest and funniest of Kitano’s tributes to the imagination and the joy of creating.

Yet when death finally comes to the gang’s personal Eden, it feels terrifyingly mundane, overturning the warm tranquillity of their photogenic retreat with unnerving indifference before leading the film into the most sorrowful, psychologically destructive series of slaughters found in Kitano’s fatality-heavy career. More than any other work from the director, Sonatine may leave you fearful for the mental stability of its helmsman but the mind-shattering impression it sustains over multiple viewings makes it easily one of the great crime films of recent decades as well as an arguable peak for one of the true mavericks of modern cinema.

Watch Now on FilmDoo:

(UK & Ireland only)