By David  Pountain

Directed by Jia Zhangke

London Film Festival review

Ever since the Chinese auteur’s poignant and delightfully lo-fi 1997 debut Xiao Wu (aka Pickpocket), Jia Zhangke’s narrative features have been operating on a consistent four or five star level that has established the socially aware visionary as one of the greatest directors of the last two decades. So while  it will likely be a prevalent opinion that Mountains May Depart is almost certainly Jia’s worst feature fiction yet, bear in mind that this still leaves a whole lot of room for quality. The director of such masterworks as Platform, Still Life and, most recently, A Touch of Sin, is evidently still one of the finest filmmakers out there at doing what he does best. It’s only when Jia dares to venture outside of his comfort zones that Mountains May Depart yields mixed results.

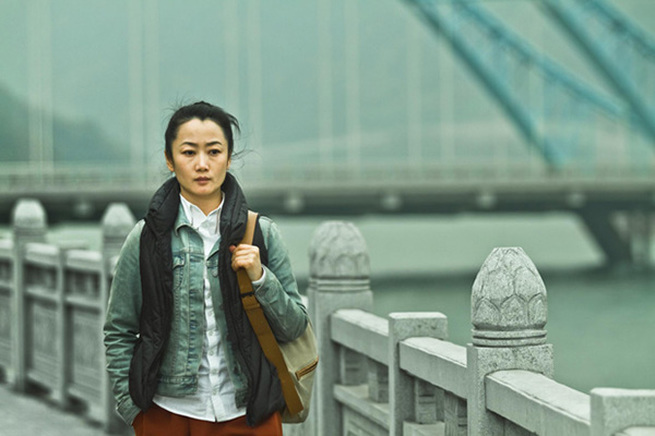

It’s certainly a work of great ambition, taking the decades-spanning structure of Platform and shifting it a few decades along to demonstrate not just where the People’s Republic has been and where it is now but also, for better or worse, where it could go. The first and best of the film’s three very distinct parts takes place in 1999, a time when the new millennium was looked upon with unrealistic optimism. Jia regular Zhao Tao plays Tao, the sunny, thematically loaded centre of a love triangle that sees her having to choose between working man Liangzi (Dong Zijan) and educated capitalist Jinsheng (Zhang Yi), a transparent microcosm of a choice that the nation as a whole took as it transitioned away from its traditional communist ideals.

Mountains May Depart is replete with symbolism that’s just a little too on-the-nose and this first part is no exception but the elegiac humanity of this extended prologue easily overcomes this shortcoming thanks in part to its naturalistic but thoughtfully precise performances. Moreover, with its saturated colour scheme, the 1999 scenes are an aesthetic pleasure that make the film worth seeing for its retro rush alone. As the section of the film that stays truest to Jia’s realist, stylistically democratic roots, it’s no coincidence that, period details aside, this is also the film’s most visually resonant third, communicating volumes with its footage of densely packed crowds and sparse landscapes.

Some of the best features of this first section partially seep through to the rest of the film. Jia keeps the visuals aesthetically attractive for the remaining running time, even if, with the exception of a stunningly pretty final scene, things aren’t on the level of part one. Similarly, while the three leads from 1999 don’t retain their prominence for the rest of the film, they remain engagingly sympathetic whenever they’re on screen.

Part two, set in 2014, isn’t quite as refreshingly distinctive as that which came before but it serves as an affecting continuation as China becomes increasingly globalised. Liangzi, ill from his work in the fading coal industry, finds himself having to borrow money and travel for employment. The wealthy Jinsheng, separated from Tao after one child, is now going by the name ‘Peter’ and arranging to send their son Dollar to a fancy Australian school, much to the anxiety of his ex-wife who fears that her only child is slowly slipping away from her. The changing times are encapsulated heartrendingly in the traditionalism of one funeral scene. This is an era of his-and-hers iPhones and instant gratification where traditionalism itself is dying.

The film only truly loses its way in the final third, in which the story moves to 2025 where grown up Dollar speaks English as a first language and the old days are a half-remembered dream. The segment fails to deliver a particularly expansive vision of the future, offering few revelations beyond its undercooked ideas of delocalisation and loss of national identity, but worse than the anaemic subtext  is the glaring reality that Jia Zhangke simply isn’t yet ready to film English language scenes. The dialogue is distractingly clunky at times and the performances, even among those who speak English as their native tongue, often fail to convince. The transcendent finale and a touching appearance from a now pitiable Jinsheng aside, part three is redeemed only slightly by a sense of detached absurdity that lies in the same hallucinatory vein as the violent genre immersions in A Touch of Sin and the buildings blasting off into space in Still Life.

Despite thematic similarities with the rest of the director’s filmography, this feels like the first Jia Zhangke feature not to slot seamlessly into his crystallised, career-spanning, ever-expanding vision of China. Jia has always had a gift for finding humanity in our most awkward, lame and pathetic moments on levels personal and national. His ability to wring profound emotion from the underwhelming has acted as a thread of continuity running through all of his narrative releases, from the anti-climactic clumsiness of Xiao Wu and Unknown Pleasures to the hollow theatrics of The World and A Touch of Sin. This thread is cut short at Mountains May Depart and it’s largely for this reason that it’s easily one of Jia’s most accessible works but also his least interesting. Despite its daring structure, this is the closest the director has ever come to playing it straight and it isn’t an especially becoming change of pace.

But, just to be clear, this is all speaking relatively. Taken on its own, Mountains May Depart is one third a great period film, one third a good contemporary drama and one third a severely flawed but sporadically engaging sci-fi. Long-time fans and newcomers alike will find plenty to appreciate in all the film’s melancholic, lopsided glory.