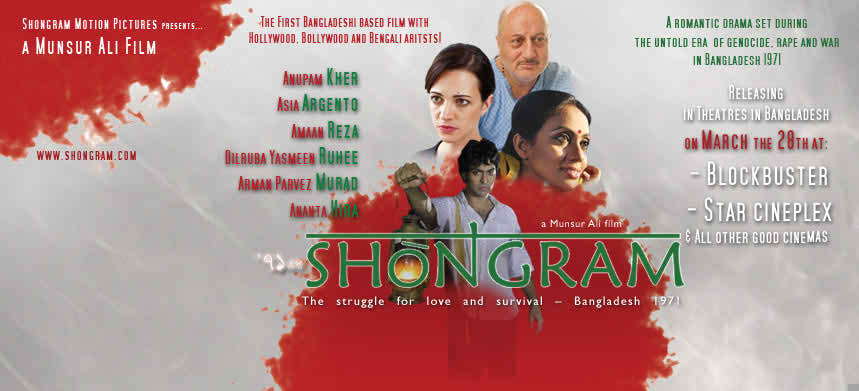

Directed by  Munsur Ali

Shongram is a Bengal film set during the heated conflict of the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971. The film follows Karim, a young and cheery man, as he goes from an innocent and carefree civilian to a broken soul mired in the conflict. During this time, he falls in love, and tries to maintain that love during the violence whilst also seeking revenge against the man who ruined his life. The film is, in many ways, about holding onto your identity – specifically through language. The conflict between Urdu and Bengal is prominent throughout, and demonstrates how speech can be used to both oppress and covert. This is about the only interesting thing going on in Shongram, however.

The film at times is fairly well-shot; scenic images of the countryside are filmed with reverence and understanding of how to best present them, no scene is ever too dimly lit or out of focus and some genuine attention has been paid to framing. It’s a shame that the presentation of the film is so atrocious that it’s hard to ever really appreciate the better moments of it'[s aesthetic. The editing seems to betray any notion of coherency, with shots going on too long, ending too soon or cutting at bizarre moments. This is not to speak of the audio editing of the film if the film looks bad, it sounds abysmal. Audio levels would often vary wildly, ambient sound would look obviously, shoddy and invasive stock sound-effects that sounded out-of-place were rampant. The editing was somehow worse; the music would cut in at hilariously maudlin and over dramatic times and disappear just as quickly, only to cut back in when a character said the magic word. Shongram was almost certainly the worst-sounding movie I have ever seen in a cinema.

The acting in the film ranges from competent to bad – though to be fair, the film itself is constantly escalating in scale. Every scene is more dramatic than the last – louder, more emotionally charged, and all without any satisfying build – so the actors are kind of backed into a corner and their only real option is hamming things up. This is not helped by the fact that characters are often incredibly broad and poorly defined – the “main villain†of the film being the worst. He is a man defined only by his love of killing – and he does so constantly. The film would easily lose thirty minutes of runtime if they removed scene after scene of he and his goons killing people. Just in case for some reason you weren’t convinced this man is in fact the bad man, the film throws in the fact that he is also a rapist, obviously. The atrocities commitment during wartime absolutely have their place on film; however they should never become mundane (or worse, simply become tools for making us hate the bad guy rather than the war itself).

The film desperately wants to tell a serious story free from the bombastic shadow of Bollywood cinema (the Director himself stated so) – however the film falls victim to many Bollywood tropes, and in such a serious story it just feels out of place. The film runs on far too long, the female lead is on occasion shamed for not immediately accepting the male leads affectionate advances, the film switches from romance to horrors-of-war at breakneck speed, the characters are broad emotion and exposition-machines and yes, there is a musical number. Despite the fact the film genuinely feels like it wants to seriously recite the atrocities of the conflict, it can’t help but slip into these cartoonish traits. The tone, if there is a consistent one, is “weepy†more than anything else and honestly, it feels like this may have been it’s intention to a certain extent.

At the film’s end, a reporter takes the “story†of Shongram to her Editor. It’s a shame that some of the best acting in the film comes from the young reporter, because it’s wasted on a monumentally aggravating scene. She speaks with her straw man Editor, who says the words “I don’t have a soul†aloud before telling her no one cares about her story. He promises to read it, and the final shot is him throwing it in the bin. That’s right, the film has the audacity to say “no one cares about this story and it will never be told†and then run the credits completely oblivious to the irony.

Cultural differences must always b e kept in mind, along with budgetary constraints; however if a film is to be taken seriously, it’s unfair to permit it leeway because of them. The bottom line is that Shongram is an ugly movie with problems right at it’s core, regardless of it’s budget and origin. When I left the Cinema showing Shongram, I ultimately left longing for a much, much better movie – because God knows the subject matter deserved it.