By Oliver Thom

One half of the greatest collaborative gift Japanese cinema has ever given to the world, Toshiro Mifune, with his 17 year, 16 film association with director Akira Kurosawa, was Japan’s principal leading man for nearly half a century. If Kurosawa was the brain behind new Japanese cinema, Mifune was its most recognisable face.

The first born son of Japanese émigrés living in occupied China, Mifune initially worked in the photographic studio of his father. Drafted at the age of 20, he spent the Second World War in an aerial photography unit in the Japanese air force, and In 1945 saw the war end while part of an educational department posted at a Kamikaze air base.

The year 1946 made Mifune an actor, if reluctantly. Arriving at Toho Studios looking to be an assistant cameraman, he accidentally walked into the interview process for a “new faces†talent hunt. Asked to laugh, he said he couldn’t, and feeling mistreated when the judges asked him to “act angryâ€, he destroyed the set. His audition was seen by filmmaker Kajiro Yamamoto and his young assistant director, Akira Kurosawa (Kurosawa had heard the brouhaha from an adjoining studio). Both were immediately smitten. Mifune was still holding out for the camera department.

Yamamoto, in recommending Mifune to a friend, secured him a debut in Senkichi Taniguchi’s Ginrei no Hate (Snow Trail) in 1947. The story of three bank robbers hiding out at a mountainside inn high above the Japanese Alps. The film was penned and edited by Kurosawa, and also starred another of the future Kurosawa-Gumi (Kurosawa Group), 21 time collaborator Takashi Shimura.

A year later, the pair would reappear on screen together in Kurosawa’s first major feature, Yoidore Tenshi (Drunken Angel), the story of a tubercular yakuza gangster and his alcoholic doctor. It was the first of a trio of films that took place in the seedy Wild West of post-war Tokyo, followed by Shizukanaru KettÅ (The Quiet Duel) and “Nora Inu†(Stray Dog).

The duo’s first period flick, RashÅmon, opened to a cold reception in its native Japan. In the West, it won an Academy Award and the Venice Film Festival’s Golden Lion. It was the film that made Mifune an international star – he had reportedly studied footage of wild lions to inform his performance, something he would repeat in the influential Shichinin no Samurai (Seven Samurai).

It was with RashÅmon and Seven Samurai that the physicality of Mifune first imposed itself, and it would reappear in four more jidaigeki (period-drama) films with Kurosawa – Kumonosu-jÅ (Throne of Blood), Kakushi-toride no san-akunin (Hidden Fortress), and the YÅjinbÅ (Yojimbo) and Tsubaki SanjÅ«rÅ (Sanjuro) duology.

If Bram Stoker’s Dracula dictated that “looks could killâ€, then Mifune could do it with a slouch. A combination of momentum and inertia, Mifune was able to use his blustering physicality in a way that laughed at human anatomy. In Rashomon he was unhinged, in Seven Samurai an idle scapegrace. In Throne of Blood as a feudal Macbeth, he lost his mind. Hidden Fortress saw him command with a martial authority, and in Yojimbo and Sanjuro he was the brooding ‘Man with no Name‘ before Eastwood ever existed.

So much of acting is done with the face – but Mifune had two, his body working on overtime as another outlet of expressive energy. He could be dominant, rampant and a rakehelly – but it made his quieter, more vulnerable moments of emotional honesty all the more affecting. Of actors since, only Nicholas Cage comes close.

More contemporary roles with Kurosawa appeared alongside his samurai exploits – he took a backseat next to Takashi Shimura in the director’s masterpiece Ikiru (To Live), his only Kurosawa outing in which he does not lead. In Ikimono no kiroku (I Live in Fear)he played a factory owner terrified of the prospect of nuclear war andin Warui yatsu hodo yoku nemuru (The Bad Sleep Well), he was a corporate Hamlet. In Tengoku to Jigok (High and Low), he was an industrialist facing extortion at the hands of a kidnapper. No one trick pony, Mifune was able to limit his physical authority for these roles, but it is for his appearances as Samurai that he will always be remembered.

It was 1965’s Akahige (Red Beard) that ended the Mifune-Kurosawa association, the natural beard that Mifune was required to grow for the role kept him from acting for over two years during the films protracted production – and it almost financially ruined the actor’s fledgling production company. It wasn’t the first time that Kurosawa’s demanding attention to detail had caused problems for the actor – he had suffered nightmares for weeks after facing a volley of real arrows shooting the climax for Throne of Blood. Kurosawa was reportedly unhappy with Mifune’s acclaimed performance, and the pair never worked together again, avoiding each other for nearly 30 years.

Of his relationship with Kurosawa, Mifune had said “I am proud of nothing I have ever done other than with himâ€, but his filmography outside of Kurosawa is still worthy of envy. He often averaged four to five films a year, and squeezed between his collaborations with the director were 1952’s Saikaku Ichidai Onna (The Life of Oharu) and from 1954 to ’56 the Samurai trilogy – a biography of Japan’s greatest samurai, Miyamoto Musashi. The trilogy further cemented his reputation as Japan’s biggest star (The leading film winning an Academy Award for best foreign language film).

His association with samurai did not stop with Kurosawa – between 1965 and 1969 Mifune starred in Samurai (Samurai Assassin), Dai-bosatsu tôge (Sword of Doom), Masaki Kobayashi’s Jôi-uchi: Hairyô tsuma shimatsu (Samurai Rebellion) and Fûrin kazan (Samurai Banners). He acted with a live sword blade during the filming of each, saying – “It has forced me to master each movement. I must be a perfectionist. It also gives me a sense of realismâ€. His physical domination on the big screen was just as real as his sword – his braggadocian swagger and command over the audience defied his 5’9†frame. Most thought he was over 6’4â€.

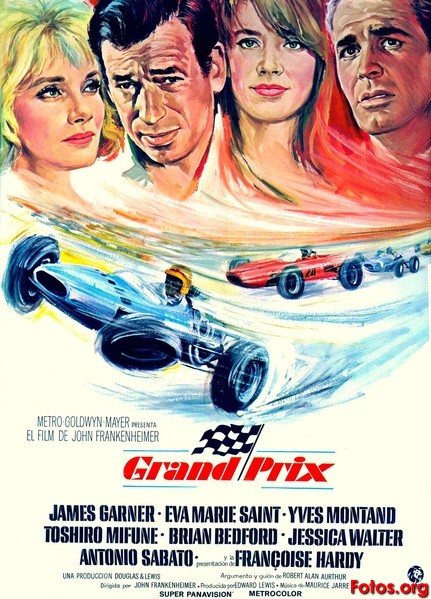

Later, Mifune made the transition to Hollywood where Kurosawa could not, first starring as a support in John Frankenheimer’s “Grand Prix†in 1966 and appearing opposite Lee Marvin in “Hell in the Pacific†in 1968. He beat up a gun slinging Charles Bronson in the Samaurai-Western crossover “Red Sun†and starred next to Charlton Heston, Henry Fonda and James Coburn in the war epic “Midwayâ€. He was almost cast as Obi Wan Kenobi (and reportedly Darth Vader) in George Lucas’ new “Star Wars†project, but turned Lucas down for the same reason Alec Guinness would later come to resent the franchise for. In 1979, Steven Spielberg cast him as a Japanese submarine captain in his wartime comedy “1941â€, and in 1980 he was a part of the acclaimed NBC mini-series “Shogunâ€. Learning his lines phonetically, he was dubbed over anyway – a disappointment he carried to the day he died.

Later, Mifune made the transition to Hollywood where Kurosawa could not, first starring as a support in John Frankenheimer’s “Grand Prix†in 1966 and appearing opposite Lee Marvin in “Hell in the Pacific†in 1968. He beat up a gun slinging Charles Bronson in the Samaurai-Western crossover “Red Sun†and starred next to Charlton Heston, Henry Fonda and James Coburn in the war epic “Midwayâ€. He was almost cast as Obi Wan Kenobi (and reportedly Darth Vader) in George Lucas’ new “Star Wars†project, but turned Lucas down for the same reason Alec Guinness would later come to resent the franchise for. In 1979, Steven Spielberg cast him as a Japanese submarine captain in his wartime comedy “1941â€, and in 1980 he was a part of the acclaimed NBC mini-series “Shogunâ€. Learning his lines phonetically, he was dubbed over anyway – a disappointment he carried to the day he died.

Toshiro Mifune starred in close to 170 films, but it will be for the 16 productions with Akira Kurosawa that he will be remembered. In 1993, they tearfully reconciled at the funeral of mutual friend and “Godzilla†director, Ishiro Honda. Kurosawa caught sight of Mifune, standing with difficulty with the mourners, walked over to him and said (roughly translated) “Are you okay? Don’t overdo, nowâ€. Mifune replied, “I’m okayâ€. It was their last exchange, and ended nearly three decades of aversion. Of Mifune, Kurosawa had said, “All the films that I made with Mifune, without him, they would not existâ€, and, as both neared the end “If I ever see Mifune again, I want to tell him what a good job he did. I want to praise himâ€. He had never done so face-to-face. He never had the chance. Always connected, they died within a year of each other. Both of them living forever in their shared work.

Seven Samurai Trailer:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xnRUHtSgJ9o]

Grand Prix Trailer :

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ziuLqY6TloM]